More Romance

More Romance

|

|

|---|

|

|---|

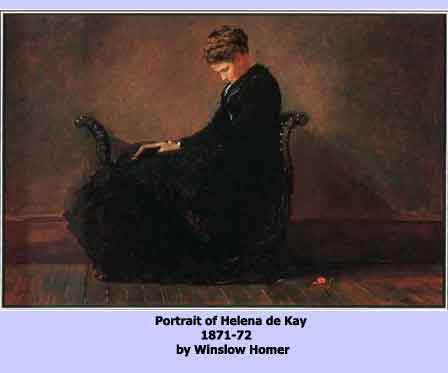

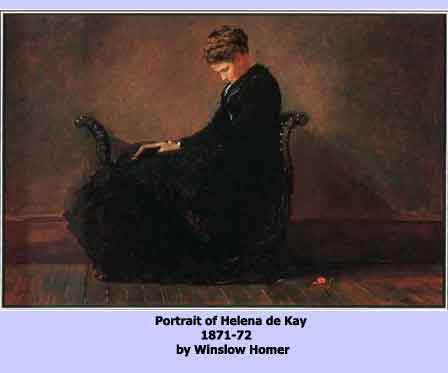

The Courtship of Winslow Homer - letters reveal relationship with Helena de Kay Despite past attempts to decode Winslow Homer's Portrait of Helena (see above), there are puzzles left to solve. Some have speculated that de Kay was the woman whose rejection don confirmed Homer's status as an inveterate bachelor. (1) However, there has been little concrete evidence to show that Homer nurtured tender feelings for the woman who ultimately became the wife of the poet Richard Watson Gilder (1844-1909). (2) Now, a newly accessible group of letters, most of them written in the early 1870s, offers proof that Homer was powerfully drawn to Helena de Kay. Not only do these letters allow us a rare glimpse into Homer's heart, but they also cast fresh light on his artistic interest in courtship and other romantic themes in the early 1870s. After de Kay was married in 1874, the subject of courtship tapered off and eventually disappeared altogether from Homer's art. Homer probably met de Kay through her brother Charles (1848-1935), who occupied Homer's studio in the University Building in New York City during 1867, when Homer was living in France. Her acquaintance with Homer must have dated to late 1867 or 1868 after the painter returned to New York City. She was then living in the family house on Staten Island but spent her days in Manhattan studying to become an artist at the Woman's Art School at Cooper Union, often in the company of her close friend Mary Hallock (1847-1938). It is not certain when Homer's romantic interest in de Kay began to stir. He may already have had her on his mind in the summer of 1868 when he painted The Bridle Path (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williams-town, Massachusetts) set in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. David Tatham has put forward a case for identifying the model as Martha Bennett Phelps (d. 1920) of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. (3) Yet in 1873, Mary Hallock, then living in Milton in Ulster County, New York, wrote to de Kay saying that when her little nephew Gerald "looks at a photograph of The Bridle Path he says 'Helena---ride--horseback.'--this is his own idea." (4) After her marriage in 1876 to Arthur De Wint Foote (d. 1933), an engineer, Mary Hallock Foote lived largely in the Far West, but she and Helena de Kay continued to exchange letters in which they shared their most intimate feelings until the latter's death in 1916. Whether or not Homer used de Kay as his model for The Bridle Path, the pretty rider looked enough like her to fool a little boy.

In 1871 Homer worked on a set of silhouettes to illustrate a special edition of James Russell Lowell's poem The Courtin'. The silhouette illustrations to various Shakespeare plays and other texts created by the Polish German artist Paul Konewka may have been the inspiration for Homer to choose this type of illustration. (5) Konewka's silhouette of the character of Helena in Shakespeare's Mid-summer-Nights Dream (Fig. 4) would have attracted Homer's attention for the name alone, and certainly the rose vine would have fixed his interest, since Helena de Kay's signature flower was the rose. When Mary Hallock married, for example, she later recalled that de Kay "sent me the red rose we called hers, her type and symbol, to wear inside my wedding dress--I have it still, a few petals empurpled with age, pressed inside an old locket." (6)

Homer's seven silhouettes for The Court-in' illustrate the progress of the Yankee Zekle courting Huldy, a farmer's daughter. In the first (above) Zekle peers through a window at Huldy, who is peeling apples. Leafless, thorny vines twine around the window frame like the roses hedging the Sleeping Beauty's castle. Gaining entrance, a tongue-tied Zekle stands abashed while Huldy asks if he has come to see her father. Finally he kisses her, after which Huldy sits "Teary Roun' the Lashes" (above), and in the final picture they stand together in their wedding finery, roses scattered at their feet. Unaccountably Lowell violently objected to the illustrations, thinking them disgusting and vulgar, particularly the wedding scene. However, it is not difficult to imagine the reticent Homer, Boston-born and bred, imagining himself as Zekle courting Huldy, an Americanized variant of Konewka's Helena. During the early 1870s Homer sought Helena de Kay's company at every opportunity. The seven surviving letters from the period detail these attempts and betray unfulfilled longing. Although some are not dated, internal and circumstantial evidence allow one to make a good guess at when Homer wrote them. At first be maneuvered to become her instructor of drawing for magazines. In the fall of 1871 or winter of 1872 he wrote: Miss Helena, If you would like to see a large drawing on wood, and will come to my studio on Monday or Tuesday, I shall have a chance to see you. Why can't you make some designs and let me send them to Harpers for you, they will gladly take anything fresh. And I will see that you draw them on the block all right. (7) Helena de Kay preferred to receive her instruction elsewhere. Accordingly, in another letter Homer wrote: "Dear Miss Helena, You know you were to let me know when it would be agreeable for me to call at your studio. Having no word from you I suppose you have made other arrangements." Later he attempted to extract a commitment from her: "My work this winter will be good or very bad. The good work will depend on your coming to see me once a month--at least--Is this asking too much? Truly yours, Winslow Homer." The most poignant letter is dated June 19 and bears the address of the Studio Building at 51 West Tenth Street. We can date this letter to 1872, the year Homer moved into the Studio Building. (8) In the letter he mentions his plan to spend a month in Hurley New York, with his artist friend Enoch Wood Perry (1831-1915). Several New York newspapers confirm that the two friends visited Hurley in June and July 1872. (9) In his letter Homer wrote: My dear Miss Helena, Enclosed find photo's which are a failure. I keep one for company this summer. You may think it will be dull music with so faint a resemblance and so dolorous but it's like a Beethoven symphony to me, as any remembrance of you will always be. He affectionately urged her to remember him through the long summer until they met again, and in closing he sent his regards to Mary Hallock and wrote, "believe me your most devoted, and true, and very sincere friend, Winslow Homer." What Homer meant by "photo's" is not clear. Perhaps they are of de Kay or perhaps of a sketch he made with her as the model. However, for the laconic Homer to compare her image with a Beethoven symphony suggests the intensity of his feeling. The sketch of Helena de Kay at the end of the letter (Fig. 5) says a great deal more than the stilted words.

Homer spent some time with de Kay that summer, although it is uncertain here they met. Possibly she visited Mary Hallock at Milton, which was only about twenty miles from Hurley An undated letter from Hallock to de Kay suggests that the meeting was at Palensville (now Palenville) in the Catskill Mountains where the de Kays spent their summer vacation. Helena de Kay and her mother had been with Mary Hallock on the farm in Milton but then went off to the Palenville house--"Mt Home," as Hallock called it. She wrote: "What an advantage to have Winslow Homer around! You'll pick up arey [ever] so many crumbs of wisdom. I do think his pictures are very masterly looking and never trivial or 'pretty"' (10)

Homer's dated oil sketches of de Kay outdoors provide even better evidence of this encounter in 1872. One of them, Butterfly (above), shows her in profile looking down at the brilliant monarch butterfly poised lightly on the back of her hand. Given the sketch above it is tempting to speculate that the butterfly is Homer's surrogate or emblem, fluttering near the heart he wished to win.

In Summer Afternoon (above), also of 1872, de Kay's fan is now folded and hangs on a ribbon from her wrist. In photographs and the Homer portraits alike a certain elusiveness is found in every image of de Kay in the 1870s. She is almost always shown in profile and never engages the viewer, but with downcast eyes she seems intensely self-absorbed or excessively demure.

A third painting in this group, Sunshine and Shadow (Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, New York City), shows a young woman lying in a hammock reading a book. The model bears less resemblance to de Kay for her hair is swept back differently and her eyes, looking up for once, seem to have a different set. The model might be de Kay but if so the unfamiliar three-quarter view of her face makes identification more difficult.

Courtship and marriage were very much on Homer's mind in 1872. In Waiting for an Answer (above) the young woman is much like de Kay in the other paintings, particularly in the cant of her head and the set of her eyes, downcast so evasively In At the Window (below) the model is probably not de Kay. Nonetheless the prominence of her wedding ring is a clue to Homer's state of mind in the summer of 1872. In Morning Glories (private collection) of 1873 the young woman also wears a wedding ring. Judith Walsh has noted that the figure looks a great deal like de Kay and has suggested that Homer used flower symbolism here to express his abiding love for her "even though she wed another." (11)

In May 1872 de Kay met Richard Watson Gilder in the editorial office of the new Scribner's Monthly, of which Gilder was managing editor. According to their daughter Rosamond the two "went to concerts and art exhibitions...listened to lectures, read poetry and studied Dante with an ever-increasing pleasure and intimacy" (12) A letter from Charles de Kay to his sister Helena in July 1872, mentions Gilder in a matter-of-fact way confirming that he was a known quantity by then. (13) Still, Gilder had not yet won the field, for it is clear that Homer still considered himself a suitor in his letter of June 19 comparing his photo of her to a Beethoven symphony However, the fourth letter, the only one previously published, is dramatically cooler. Dated December 22, 1872, it reads: My Dear Miss Helena, If you would like to give your mother a Christmas present of that sketch I painted from you I will give it to you with pleasure. Why don't you limp into my studio on your way up or down and take it. I am very jolly, no more long faces. It is not all wrong. Yours sincerely, W H. The underscored "to you" suggests that she had been avoiding him. Whether de Kay had told him of her attachment to Gilder or he had heard about it some other way Homer made no secret of his unhappiness and resentment. It was all in vain. (14) By May 1873 his successful rival was writing love sonnets, which were published in Scribner's Monthly in November. In February 1874 the couple announced their engagement, and in June they were married. (15) Scholars have assumed that the "sketch" Homer mentions in his letter was the painting at the top of the page. Given the fact that he made several sketches of Helena de Kay there is no reason to suppose that this assumption is correct. He did give the Portrait of Helena de Kay to the sitter; but it may not have been until the time of her marriage. And she may never have come to his studio to claim the picture he wanted her to have at the end of 1872. There are problems dating the Portrait of Helena de Kay. It is inscribed "June 3, 1874," the date of her wedding, and initialed "W. H." However, when it was exhibited at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City in 1936 and 1937, the catalogue stated that it was dated "June 3, 1871." and recently Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. has argued that this is a more plausible date. (16) However, given Homer's romantic hopes in June 1872, why would he have produced such a funereal image so early? It is doubtful that he began the painting before the autumn of 1872, when he must have realized that de Kay preferred Gilder. Most probably Homer painted the portrait as an elegy for his dead romance, and he crafted every detail to tell the tale of his rejection. He took particular license with her costume, for although a certain gravity was characteristic of her, she seldom ever wore black, at least as a young woman For example, one Christmas Mary Hallock sent de Kay a jacket she had made for her, remarking that there was nothing practical about it except for the colors, "your own colors, the pure and passionate white and red which I love for your own sake." (17) On another occasion, Hallock wrote to Richard Gilder about how a statue of "Saint Helena" might be dressed two centuries hence: "In a warm dark brown with goldy lights and little gleams of pale yellow here and there or a hint of pure red." (18) But in Homer's portrait de Kay is muffled to the chin in dead black relieved only by a sliver of whit frill at the neck. She is more like a widow a bride. The rose, as we have seen, was de Kay's special flower, yet here it lies bedraggled on the floor, a couple of petals torn away Judith Walsh is no doubt correct in interpreting this rose as the generic floral symbol of love, Homer's in this instance, cast o and left to wilt and die. (19)

The closed book she holds in the painting may also have conveyed a personal meaning for Homer. The illustration he did for Harper's Weekly in 1868 (see above) features romantic couples of kinds surrounding a modem American couple at the center. The man's handlebar moustache is much like Homer's own. At the lower right four busy cupids are grouped around a large pillow on which reposes an pen book inscribed with a "W" and an "H" on facing pages. De Kay has closed this book the book of Homer. Could there be a more woeful wedding present than this reminder of wounded love and the road not taken? Only one of the letters express the same sense of injury so nakedly It is dated but was probably written in late 1872 or early 1873 when Homer's feelings were still raw. There is no salutation. The body of the letter says only "Go and see your clever picture. It was painted for you to look at. Respectfully yours Winslow Homer." The ink is smeared as if he dashed off these words in haste without stopping to use a blotter. Underneath the signature are the words "to my runaway apprentice." We may never be able to determine which picture Homer meant, hut surely its message was one of anger and reproach. By May 1873 Homer had managed to recover some equilibrium. De Kay was still friendly, inviting him to a gathering at her studio that month. But Homer kept his distance, writing back on May 20: "I must refuse your invitation for Sunday Will you pardon me? If I expect to do anything this summer I must not lose any more time and patience in New York." He announced that he was preparing to leave for Gloucester, Massachusetts, to "make another fortune... .Until then I shall be very busy. So I say goodbye, and wish you all kinds of good luck. I shall paint for your approval. Your friend, Winslow Homer." A hand injury prevented Homer from leaving as planned, and he was still in New York at the beginning of June when de Kay sent him one of her flower paintings as a present, perhaps as a peace offering. Homer's letter of June 3 thanking her reveals how much he still cared for her: My dear Miss Helena, I have just found your picture. I think it very fine. As a picture I mean, not because, etc. and as I have just returned from Prospect Park where I have been with Mother all day, looking at the flowers, it must be fine if I think so. I thought of you once today and picked out a little girl (one of about fifty) as looking as you perhaps looked--She could outrun all the others, and gave the teacher the most trouble--and I doubt if she went to Sunday school, but she was nice. My hand is all well now, so I shall leave town immediately. I am very grateful to you. Sincerely yours, Winslow Homer The next year, 1874, Homer revisited the history of his courtship in a series of paintings that dealt ironically with thwarted love. The Rustics (private collection) and Rustic Courtship (private collection) are variations on the theme of the social barriers that finally contributed to Homer's defeat. Cosmopolitan and well to do, Helena de Kay enjoyed a life of privilege that may have alienated the more plebeian Homer. (20) In the first painting the young farmhand holding a rake and a small bouquet of roses stands below the open window that frames a housemaid with a feather duster. She is unattainable, for though the window is open the walls are thick. In Rustic Courtship the farmhand stands directly under the window and much closer to the wall. This only emphasizes the housemaid's superior position. Another painting, the now unlocated Course of True Love of 1875, dealt directly with humiliation. It depicted a farm girl chewing on a straw and sitting in a field with her back to her suitor after some argument. As one newspaper described it, "Her lover, a manly looking fellow, is twisted about, embarrassment peeping from every feature and even from the toes of his cow-hide boots." (21) The fact that Homer recast de Kay as a housemaid or a blowsy country lass is indicative of his desire to distance and protect himself from painful memories.

Girl in the Orchard, by contrast, suggests that at some level Homer never ceased to regret his failure to make de Kay his wife. This is a sequel to Waiting for an Answer, painted two years earlier. It is the same scene with the crucial difference that the young farmer has disappeared, leaving the hesitant, downcast girl still dangling her straw hat, its ribbons stirring gently in the breeze. A rooster and two chickens are her only companions. Homer kept this painting all his life. He hung it in a cottage he had built in 1901 in Kettle Cove, Maine, which was part of the Homer family compound by the sea. Although he rented out this house and never lived there himself, Homer thought of it as the place where he would end his days. He declared that "Other men build houses to live in, I build this one to die in." (22) Helena de Kay for her part kept the Homer portrait (at the top) all her life. Over the years the painting lost its sting, at least as far as the Gilder family was concerned. At one point their son Rodman (1877-1953) mounted a photograph of the portrait on a little calendar, a copy of which he sent to Mary Hallock Foote. Helena de Kay Gilder had a long life as a wife, mother, and artist. She played a key role in forming the Society of American Artists in 1877, organized a lively intellectual salon in the Gilders' house on Union Square in New York City, and later became a social and cultural star in Marion, Massachusetts, an art colony near New Bedford. When her husband died in 1909, a year before Homer, Mary Hallock Foote wrote her a heartrending letter of consolation: I look up and see you, in the little calendar Rodman gave me--he may have forgotten--your photograph from Winslow Homer's sketch. It is exactly like you--when the 'past' was difficult! I might be looking at you as you are now. Only. Dearest, I hope that you would let me take and hold one of those hands that have closed the book. (23) Mary Foote correctly understood the meaning of the book, not only with reference to Homer but more generally as an emblem of a sad and irreversible ending. For Homer in the early 1870s that ending set the course of his life as an inveterately single man. He may have had other flirtations, for several attractive young women appear in his paintings up to about 1880, but he remained solitary. From his fifties into his early seventies Homer traveled widely and turned to increasingly somber, elemental subjects in his art. Whatever scars marked him he had long since covered with the crusty shell that contributed to his undeserved reputation as a belligerent artist-hermit. But the fact that he never let go of Girl in the Orchard suggests that those scars had struck to the bottom of his soul. SARAH BURNS is the Ruth N. Halls professor of fine arts at the Henry Radford Hope School of Fine Arts at Indiana University in Bloomington. (1.) See Nicolai Cikovsky Jr. and Franklin Kelly, Winslow Homer (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and Yale University Press, New Haven, 1995), pp. 122-123; and Helen A. Cooper. Winslow Homer Watercolors (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and Yale University Press, New Haven, 1986). p. 51, n. 44. Joseph Stanton, "Winslow Homer, Helena de Kay, and Richard Watson Gilder: Posing a Rivalry of Forms," Harvard Library Bulletin, vol. 5, no. 2 (Summer 1994), pp. 51-72, speculates at length about the relationship, using as primary evidence the Homer portrait and Gilder's poetry. (2.) For their courtship and marriage, see Letters of Richard Watson Gilder, ed. Rosamond Gilder (Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1916), pp. 55-61. (3.) David Tatham, From Paris to the Presidentials: Wins-low Homer's Eddie Path, White Mountains," American Art Journal. vol. 30, nos. 2 and 3 (1999), pp. 43-44. (4.) Mary Hallock to Helena de Kay, September 1873, letter no. 43, folio 16, box 6 (Mary Hallock Foote papers, department of special collections, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California). For the friendship of the two women, see A victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West: The Reminiscences of Mary Hallock Foote, ed. Rodman W. Paul (Huntington Library, San Marino, California, 1972). (5.) David Tatham, Winslow Homer and the Illustrated Book (Syracuse University Press, Syracuse, New York, 1992), pp. 105-109, offered a detailed discussion of Homer's work on "The Courtin," including the likelihood that Konewka's silhouettes furnished Homer with a useful model. (6.) Quoted in Victorian Gentlewoman, p. 105. (7.) The eight letters from Homer to de Kay are in the Gilder manuscripts, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, and are quoted here by permission. he last letter, written in 1886, is a formal thank you to "Mrs. Gilder" for alerting Homer to the opportunity of reproducing his work in the Book of American Figure Painters. The painter John La Farge (1835-1910) was de Kay's s special mentor in the 1870s. (8.) Annette Blaugrund, The Tenth Street Studio Building: Artist-entrepreneurs from the Hudson River School to the American Impressionists (Parrish Art Museum, Southampton. New York, 1997), p. 75. (9.) New York Evening Post, July 8, 1872; and New York Evening Mail, October 18, 1872. (10.) Letter no.15, folio 14, box 6 (Foote papers). (11.) Judith Walsh, "The language of flowers and other floral symbolism used by Winslow Homer," Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. 156, no. 5 (November 1999), p. 714. (12.) Letters of Richard Watson Gilder, p. 56. (13.) Charles de Kay to Helena de Kay, July 26, 1872 (Richard Watson and Helena de Kay Gilder papers, Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C., microfilm roll no. 285). (14.) Walsh, "The language of flowers," p.713, suggests that de Kay's mother may have discouraged her daughter's interest in Homer. (15.) Letters of Richard Watson Gilder, pp.58-60. (16.) Cikovsky and Kelly, Winslow Homer p. 123. In the sonnet "Love Grown Bold," published in The New Day (New York, 1876), p. 15, Richard Watson Gilder wrote that the portrait was made before he ever met his wife. However, he was probably taking poetic license in this matter. (17.) Hallock to Helens de Kay, 1869-1872, letter no. 16, folio 14, box 6 (Foote papers). (18.) Hallock to Richard Watson Gilder, November 1873, letter A-2, scrapbook OS-i (ibid.). (19.) Walsh, "The language of flowers," p.713. (20.) Walsh reads Homers Moming Glades as an expression of Homer's sense that de Kay's elite status formed a barrier between them (ibid. p. 714). (21.) Appletons' Journal, May 8, 1875. (22.) Quoted in William Howe Downes, The Life and Work of Winslow Homer (1911; Dover Publications, New York, 1989), p.115. About Girl in the Orchard, see The American Collections (Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, in association with Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1988), p.4. (23.) Mary Foote to Helena de Kay Gilder, January 1, 1910, folio 37, box 7 (Foote papers). COPYRIGHT 2002 Brant Publications, Inc.

|

|---|