Emma

Emma

|

|

|---|

|

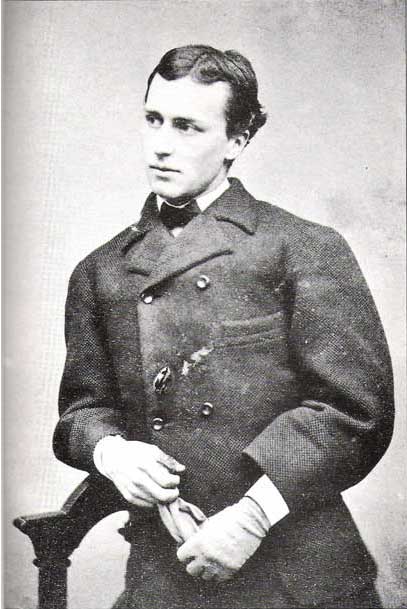

In 1883, a Pedestal Art Loan Exhibition was held to raise funds for the Statue of Liberty's pedestal. Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, and others contributed original manuscripts, but the highest bid of $1,500 was received for a sonnet "The New Colossus" written just a few days earlier. The immortal words were penned by young Emma Lazarus, soon after her return from a European trip where she had seen the persecution of Jews and others first hand: Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, It was not until 1888 that the Statue of Liberty assumed her majestic place in New York's harbor. Sadly, Emma Lazarus didn't witness this historical event since she died of cancer a year earlier, when she was only 38 years old. Actually, Emma's poem might have been forgotten, but for the efforts of Georgiana Schuyler, who had the words inscribed on a tablet and affixed inside the Statue of Liberty in 1903. In 1945, the tablet was moved from the second story landing to the Statue's entrance, where it can be seen today. |

|---|

"On a visit to New York City in the spring of 1883, Henry James made a friend of Emma Lazarus. The circumstances of their meeting are obscure, but very likely they were brought together by mutual friends, Richard Watson Gilder, brilliant editor of the monthly magazine, the Century, formidable rival of the Atlantic, and his wife, Helena de Kay Gilder, an accomplished artist. A testimonial dinner for the Italian Shakespearean actor, Tommaso Salvini, on April 26th has been suggested as the occasion on which the two authors were introduced; both allegedly attended with other "luminaries of the Century coterie" (Kessner 53). Henry, we know, was present that evening, but there is some doubt whether Emma was, for she did not read the English translation she had prepared of Salvini's speech--it was read by another guest. Or perhaps the venue was the Gilders' home. In the 1880s and 1890s, Richard and Helena presided over a salon where they assembled some of the day's most eminent men and women of letters, the arts, the stage, and society. Emma was a regular visitor to this elite circle; Henry presumably would wish to see his friends at home and would relish the chance to chat with some of his great contemporaries. One of what Emma called Helena's "Friday evenings" might well have been the setting of Henry's introduction to the "Laureate of the Jews," six years his junior, whose celebrated sonnet, "The New Colossus," would grace the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty twenty years hence. One topic the two writers surely talked of when they were introduced was Emma's forthcoming trip to England where she hoped to meet literary greats, especially Browning for whom she had profound admiration: "what a great, great man he is!" she once commented to Helena Gilder (Young 160)." from "The Master and the Laureate of the Jews: The Brief Friendship of Henry James and Emma Lazarus" by Alan G. James |

|---|

|